Written by Jem Snowdon, with edits from Hooked on Hedonism

Welcome readers, to our first guest post! Jem brings you a tale rich in murder and seduction in seventeenth-century France! So, if you want to know more about court gossip, love potions and conspiracy, then read on!

The Affair of the Poisons (1677 – 1682) was a major murder scandal in France during the reign of Louis XIV. Over the course of a vast inquiry, a large number of people, including many aristocrats and close associates of the king, were accused of murder, witchcraft and treason. Not only did this result in as many as thirty-four executions, and a great panic from the courtiers that they would be next to be killed, the affair itself, and its consequences, would leave their mark in French history for years to come…

The first whispers of the poisonings began in 1676, following the trial and execution of the Marquise de Brinvillers, the daughter of a high-ranking state official, and the wife of a wealthy nobleman.

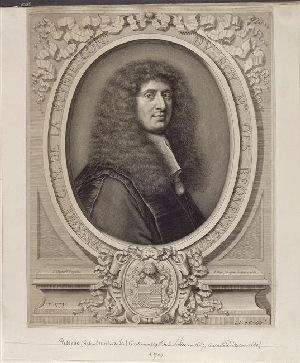

Together with her lover, Godin de Sainte-Croix, the Marquise was suspected of having killed her father and her two brothers in order to benefit from their inheritance, and to have tested the poison she used for their deaths on unsuspecting patients at a hospital. After Sainte-Croix’s death in 1672, nine letters were discovered containing incriminating correspondences between the two lovers, and vials, which were revealed to contain poisons that would leave no trace in their victim. With suspicions of foul play in the deaths becoming increasingly widespread, the Marquise fled to London, and in 1673 was condemned to death in absentia. She was ultimately found in a convent in the Netherlands in 1676, where amongst her possessions a series of letters were found, in which she confessed to her crimes, heavily contributing to the judgement of the court (despite denial of her involvement at her trial), she was condemned to torture and execution for her crimes. In July of the same year, the Marquise was decapitated with a sword, and her body was burned in public. However, the authorities were unconvinced that she could have acted alone, and became concerned that her involvement in such scandalous matters suggested that other nobles had similar criminal links and motivations. The king and many others of high rank worried that they too could be poisoned, and the lieutenant of police, Gabriel-Nicholas de la Reynie, opened an inquiry into the Marquise’s possible accomplices.

The affair is properly considered to have begun in February 1677, with the arrest of Magdelaine de la Grange for forgery and murder. Hoping to be able to save herself from execution, de la Grange appealed to the minister of war, the Marquis of Louvois, and claimed that she had information about other important crimes. He informed the king of the situation, who in turn informed la Reynie and exhorted him to find and deal with those implicated by this information. La Reynie, seeking to assure the king, then began an investigation into the matter, over the course of which links between la Grange and other known poisoners were established. The arrest of one especially notorious criminal, who was alleged to be poisoning people at the instigation of certain noblewomen, brought to the attention of the authorities the name of Catherine Monvoisin, née Deshayes. Better known by her notorious nickname “La Voisin”, Monvoisin had apparently turned to practices of fortune-telling and witchcraft to supplement her family’s income after the failure of her husband’s trade business.

This practice had gradually evolved into providing aphrodisiacs and poisons to her clients, and had granted her wealth and fortune (pun intended!). Hence, on the 12th March 1679, she and some of her accomplices were arrested, and interrogated under the influence of alcohol and torture. Amongst them were a number involved in fortune-telling and witchcraft – but their confessions quickly demonstrated that their practices were more than just the work of the charlatans so common at the time.

Over the course of the inquiry, la Reynie discovered that there existed a staggering network of such criminals in Paris. This circle included poisoners, sorcerers, fortune-tellers, alchemists and people providing abortion; activities which were all illegal at the time in France. Most shocking of all was the revelation that many of those implicated in the sordid business were of the highest echelon of French society. La Voisin’s clients included countesses, duchesses, the Duke of Luxembourg, and two of the nieces of the King’s chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin. Concerns about the safety of the king and other members of the nobility subsequently exploded, and further arrests were made. At this time, La Reynie reestablished «La Chambre Ardente», or the “burning court”, in order to investigate the affair and judge those implicated in it. This court was composed of twelve high-ranking magistrates and had as its first task the judgement of La Voisin and her accomplices. The defendants, afraid for their lives, and in many cases under duress of torture, admitted to all sorts of crimes – despite a general lack of tangible proof to substantiate many of their confessions. Amongst the various reprehensible acts they admitted to, we see murders, the sale of poisons, the summoning of demons, the killing of children during black masses, and other equally shocking and disturbing things. Thinking that the magistrates would cover up the affair in order to protect the reputation of the nobility, and taking this as the final chance they were likely to have to save their own lives, those arrested denounced their famous clients.

The list of the incriminated was not only scandalous for the sheer number of those upon it, but because of the high rank – and, in many cases, closeness to the king – of the people found to be involved with such criminal practices. Two notable examples are the Countess of Soissons, and Eustache Dauger de Cavoye. The Countess of Soissons was one of the nieces of Cardinal Mazarin, chief minister during the minority of the king, and alleged to have been the former mistress of Louis himself. Eustache Dauger de Cavoye, meanwhile, had been the heir of a powerful noble family, but had been disinherited after having celebrated a black mass, after which he began selling poisons. His sudden disappearance after the scandal led to suspicions until recently that he may have been the Man in the Iron Mask. The implication of such notable figures, and the immensity of the hysteria that came about as a result, left Louis worried that the reputation of his court was falling into ruin. As a consequence, he advised voluntary exile to those worst-affected, and finally suspended the work of the Chambre Ardente in 1682. And there was another more personal reason for the king to wish to put a hasty end to the inquiry.

Documents of La Voisin’s made reference to a link between her and the Marquise de Montespan, the most celebrated mistress of the king, and the mother of seven of his illegitimate children.

Notwithstanding the paper trail, this information did not come to light until after the so-called sorceress had been burned alive in public for her crimes on the 22nd February 1680. After this, her daughter, Marie-Marguerite, contacted La Reynie, and informed him that her mother and Montespan had been implicated in certain crimes together. In reality, it’s unlikely that the Marquise did more than consult La Voisin for horoscopes. However, according to Marie-Marguerite, the two women had taken part in black masses together in order to maintain Louis’s affection – a ceremony which involved infant sacrifice – and had moreover used love potions to help Montespan win the love of the king. It was additionally alleged that La Voisin and the Marquise had planned to kill Louis together, together with his new mistress, the Duchess of Fontanges, going so far as to attempt to offer him a poisoned petition in 1679. From the time of the first allegations against his lover, Louis and his ministers reacted to protect her. Initially, he asked the magistrates to keep documents relating to her investigation separately in a sealed box, before ordering the halt of all inquiry into matters implicating Montespan. When the judges did not listen to this request, the work of the Chambre Ardente was suspended, and the affair hushed up as much as possible to avoid further scandal around the mistress of the king. Unfortunately, the severity of the case had already resulted in some magistrates losing their caution, and inflicting severe punishments on the guilty – especially those without powerful links in court – despite a frequent lack of tangible proof of any real wrongdoing. From the 10th April 1679 to the 21st July 1682, 442 people were accused and 367 were arrested, of whom 218 were held. A total of thirty-four people were executed, with a further two dying as a result of torture; five, meanwhile, were sent to the galleys, and twenty-three were sent into exile.

As for the consequences of the Affair of the Poisons over the long-term, there are two in particular which merit mentioning, one of which can truly be considered an incredible trick of fate. Firstly, in order to suppress the practices of poisoners, and to prevent similar problems from occurring in the future, Louis put out an edict. This made of poisoning specifically a capital crime in its own right, and also limited access to toxic substances such as arsenic, so that only apothecaries and doctors could use them. The king’s decree can be considered the precursor to similar modern legislation controlling the sale and purchase of poisons, and the first of its kind in Europe. Secondly, whilst the Countess of Soissons was one of those exiled as a result of the scandal, her son was not – and he was going to change the course of history. Originally destined to be a priest, François-Eugène de Savoie-Carignan sought permission to join the army from the king at the age of nineteen. However, due to the disgrace of his mother, which had left Louis uninclined to show any compassion to her children, he was rejected out of hand. Holding a grudge against Louis, he therefore made the decision to move from France to Austria in order to pursue his ambitions: where, finally, he became a military commander for the great enemy of France, the Holy Roman Empire. There known as “Prince Eugene of Savoy”, he enjoyed a military career spanning six decades in the service of three emperors. His exceptional skill both on the battlefield and in diplomacy, though disputed in his later years, was certainly one of the contributing factors in the failure of French attempts to establish political and martial hegemony in Europe over the following years.

If you loved this tale as much as we do, find more reading suggestions on the websites resource page!